That spring, fatherls business was not good. Father came back angry from the market, as more than half of the herd was unsold and, as usual when he was angry, he swore and went to bed without taking a bite.

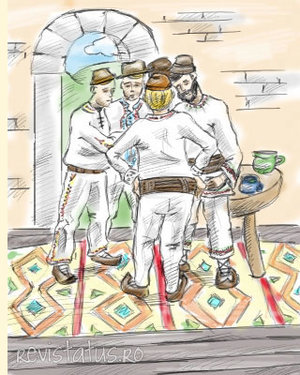

Next day, all the neighbouring cattle farmers gathered with father in the big room downstairs, poured wine and began to deliberate. They were all true cow herders, had hundreds of cows in their stables, bathed twice a year, at Easter and Christmas, drank brandy as if it were water, swore terribly and wiped their greasy lard knives on their trousers. They were not evil people, however, and there was always sugar in their pockets to give to horses and kids. They faced big competition for their herds; when going to the marketplace they had to sell their cattle well below cost or return home with it, while folk from the Milk Valley sold theirs immediately, their cattle being s’ender, with long twisted horns, gave lots of excellent milk; and what's more, it was believed that their cows were grazing at night and that's why they gave so much milk.

However, those who buy them mix them with the other cows in the herd and bring them to graze during the day, and then they give milk just like all the other cows; so why do they buy the cows from them? "Because of their reputation," Dad said, with anger, and all heads mumbled, still puzzled: "reputation."

Immediately, I thought about Luke. We were going to the same school and were friends. He was from the Milk Valley and has even asked me to come over and visit one day. I had to go to find out the truth. I set out on a holiday, and went part of the road on foot and part by train to arrive at the Milk Valley. The village was situated on a plateau opening into a large and wide valley, cut by three rivers that would join further up into a single river, surrounded by reddish, barren hills.